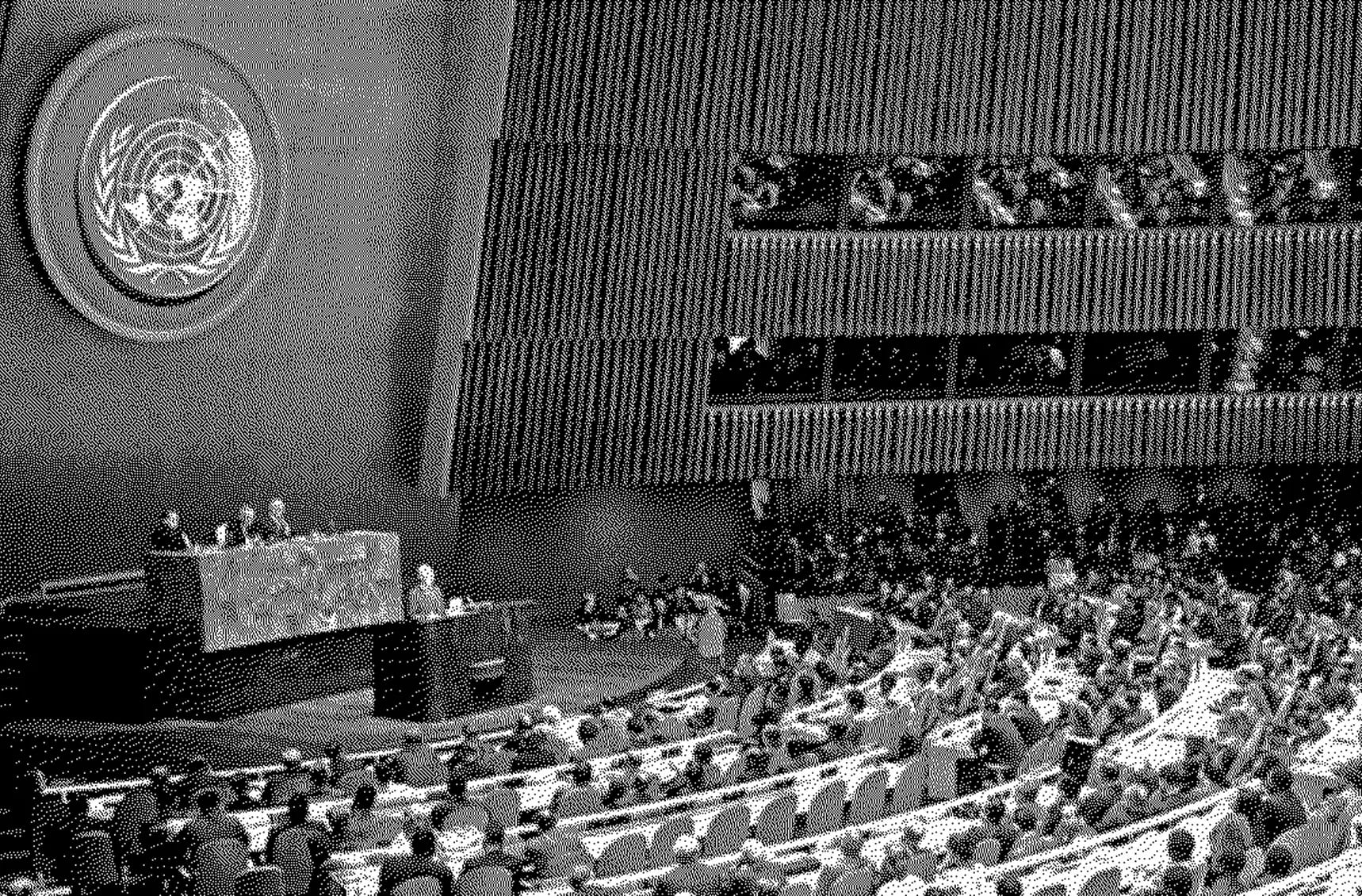

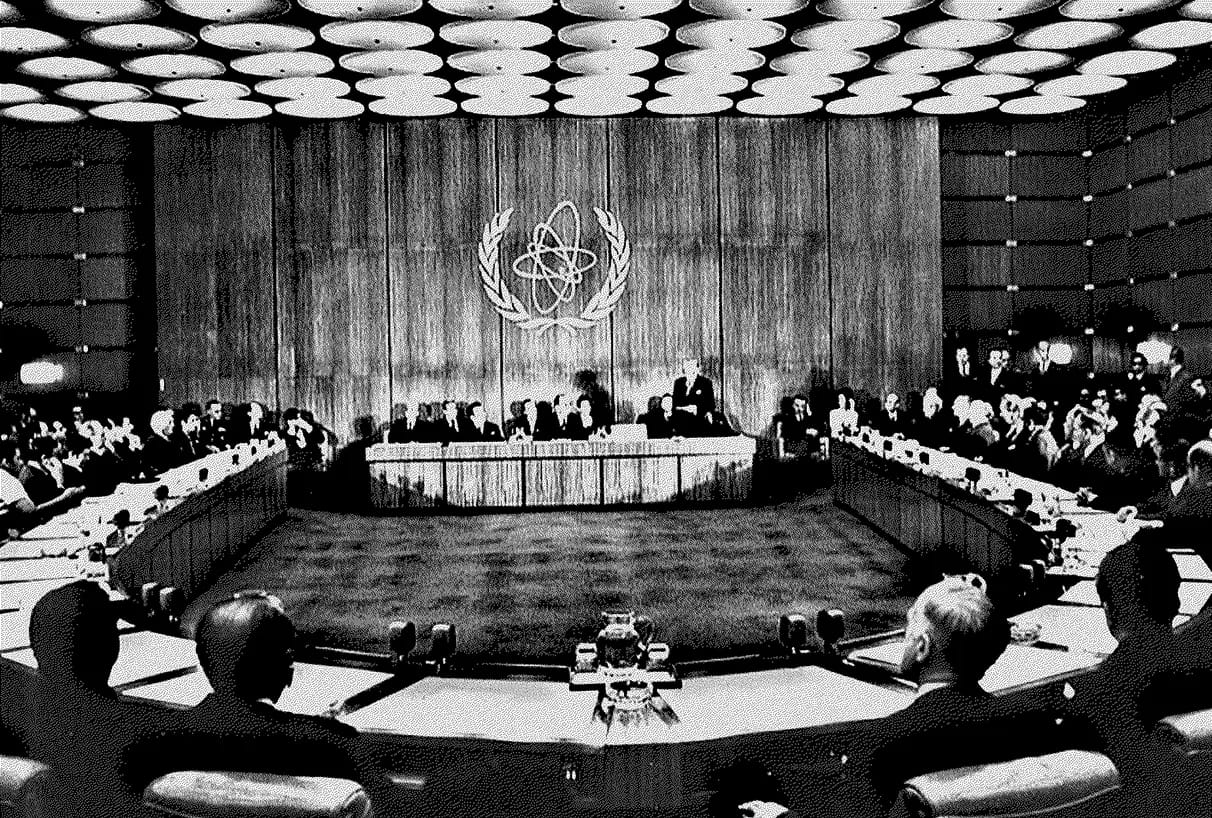

In 2021, about 275 international inspectors scrutinized items across over 1300 nuclear facilities around the world. 4 States may grouse, but the system works.

The IAEA as proto-planetary institution emerged at the confluence of specific tipping points: moments when collective risk forced states to cooperate under new frameworks. Understanding this history helps us assess whether today’s planetary challenges might create conditions for new, more comprehensive institutions.

Tipping Point: A critical threshold at which a tiny perturbation can qualitatively alter the state or development of a system.

— Lenton, Timothy M., et al. “Tipping Elements in the Earth’s Climate System.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 105, no. 6, National Academy of Sciences, Feb. 2008, pp. 1786–93, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705414105. Accessed 15 July 2025.